There are quite a few text corpora readily available in the standard NLP python packages (NLTK has quite a few). However, using those corpora would gloss over the practical issues that arise from real world data, which I think are worth discussing. Instead, I am using a Kaggle dataset of Huffington Post news headlines and scraping the text of those articles to build a corpus.

Acquiring Data

Let’s dive right into the dataset and see what it looks like.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_json('data/News_Category_Dataset.json', lines=True, orient='records')

df.head()

This dataset was primarily intended to predict news categories from headlines. From the kernels on Kaggle it doesn’t appear many people are scraping the article text itself, so let’s take a look at the links themselves to make sure they’re what we want before starting to scrape and parse the links. From the head of the DataFrame above, it looks like this dataset is sorted by date. Grabbing the top few links is thus not a random sample from our dataset (and thus we shouldn’t try and make generalization about the dataset from them), so instead let’s actually look at some links at random and proceed from there.

import numpy as np

for idx in np.random.choice(range(len(df)), size=20):

print(df.loc[idx])

Running this a few times yields a reasonable confidence that we’re seeing any substantial issues in the data, and one major problem does stand out. There are links, like the one highlighted above, that are clearly invalid. They all appear to be a link to different website appending to the back of the main URL for HuffingtonPost. Let’s see how big a problem this really is. The regex pattern below searches for links that have another http:// or https:// after the initial HuffingtonPost URL.

import re

p = re.compile('(?<=https://).+(?=(http://|https://))')

double_link_idx = df[df['link'].apply(lambda x: p.search(x) is not None)].index

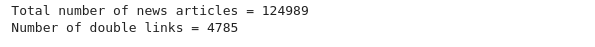

print(f"Total number of news articles = {len(df)}\nNumber of double links = {len(double_link_idx)}\n")

We could pull out the real link with another regex pretty easily, but there are about 4,700 issues of ~125,000 articles total. Considering we’d have to write a new parsing strategy in BeautifulSoup for each different site, this is not worth it for the purposes of this blog post. So let’s just drop these and move on with the parsing.

Parsing

Before running the actual scraper, we need to figure out how to extract the main text from the HTML that we’ll get back from HuffingtonPost. There are a lot of how-to blogs online for using requests and BeautifulSoup, so I won’t be going into too much detail. However, it is worth noting the higher level approach used when parsing a very large number of web pages with unknown format.

Using the Chrome inspector and manually investigating a few links will yield an initial hypothesis for what expression we can use to pull out the main text. The first pass was based on the finding that the main body was in a section with a particular id value, “entry-body”.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from fake_useragent import UserAgent

ua = UserAgent()

response = requests.get('https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/avocado-feel-full-overweight-lunch_us_5b9dc55de4b03a1dcc8cae44', headers={'User-Agent':ua.random})

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text)

string = " ".join(soup.find("section", {"id":"entry-body"}).stripped_strings)

string

This looks like what we need, however running for a random sample of 100 web pages, it fails for ~ 40. Investigating some of those failues shows us that not all web pages actually have this tag, so instead of returning the article body, our expression raises an exception. Needless to say our attempt at parsing these pages didn’t cover all cases, so let’s look at some failures and come up with an alternative.

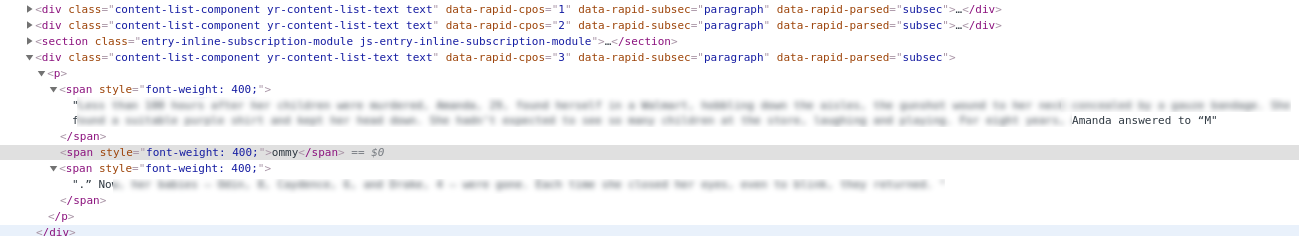

In the failures body divs were marked by class, however simply making that change failed due to very odd parsing within each paragraph div. Sentences weren’t always in their own element, and as you can see above (the text is blurred, because it was a good example, but an absolutely horrific crime), sometimes even words were split across elements. This means our logic would parse them as multiple words.

After a few more iterations, it appears that we can concatenate all strings without a space inside a certain tag, and we need to insert a space when joining strings above that in the DOM hierarchy. Since our first parser failed on the this second page type, the final parser just uses a try/except to get the correctly parsed text. If this try/except strategy covers all cases we’re in great shape, if not we may need another parser and some additional logic to determine which one to use per page. Let’s test this logic on a larger sample to see if we are ready to proceed.

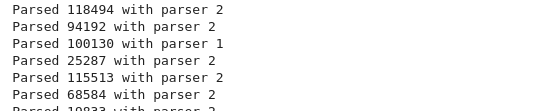

for idx in np.random.choice(range(len(df)), size=100):

link = df.loc[idx,'link']

response = requests.get(link, headers={'User-Agent':ua.random})

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text)

try:

processed_text = " ".join(soup.find("section", {"id":"entry-body"}).stripped_strings)

print(f'Parsed {idx} with parser 1')

except:

try:

processed_text = " ".join([''.join(x.stripped_strings) for x in soup.find_all("div", {"class":"content-list-component"}) ])

print(f'Parsed {idx} with parser 2')

except:

print(f'Failed to parse {idx}')

Running on a 100 random links has yielded success! To make sure the these are parsing correctly, I also wrote these to files to inspect (not shown in the code above). Now that we’re feeling good about our parsing logic, let’s move on to running this for our entire dataset.

Running At Scale

Now since there are ~120,000 articles and everyone has other things to do today (and this week) than watch HTTPS requests fly one at a time, we’ll be using asyncio to get the text of these links. If you are not familiar with asyncio, it’s worth looking into, however it’s not the point of this blog post. Dan Bader has a great tutorial on it here, and you can also see the code on my Github page here, but I won’t be talking about the implementation details in depth.

The HuffingtonPost robots.txt doesn’t show any page per minute limit nor does the /entry/* route seem to be on their disallow list, so I initally tried to scrape without any special rate limiting, however received a lot of failures with 429 status codes (too many requests). Eventually I added a sleep of 30 seconds between batches of 600 articles, which appeared to work well. For this volume, handling failures is important (especially in identifying misparsed articles as mentioned in the section above), so all failed fetching, parsing, and file writing was logging into a csv file that could be easily inspected and reprocessed. This could also have been handled by consuming from a queue, and if this was a production system running regularly/continuously I would highly recommend that. However for our purposes rerunning slightly modified code was the quickest way to acquire this dataset.

Inspecting the results showed ~4,000 articles with 0 byte size- these were all (based on manually inspecting a sizeable sample) 404 error pages (easy to add logic to drop in code) or redirects to a category homepage with no article (harder), so they were dropped. Also notable was the fact that many articles had very small sizes (a sentence or two), these were typically videos with only a caption in the main portion of the ‘article’. With the goal of classifying stories by the body, these may be more noise than signal. However, let’s just make a note and leave them in the dataset to explore them as an interesting subgroup.

Wrapping Up

Here is a quick summary of some key challenges we encountered that are often present when acquiring your own data:

- Data quality- The links themselves were often not valid, or not pointing to the domain we expected.

- Changing webpage structure- If there are no APIs available, web scraping at scale can involve a lot of trial and error. Tags and classes used by a single website can change over time or by what section of the site you’re visiting. Effective error handling and iteration is the only way to get good results.

- Rate limiting- If you’re getting web data, you need to know how to indentify and handle rate limiting and throttling. Robots.txt files give you good guidance, but as we saw here they are not always complete.

- Transience- Some of this data is simply not available anymore. There were some 404 errors, some of the time we just received a redirect to the wrong page, and some times we found that the ‘article’ was really just a video with a small caption. It’s not always as obvious as a 404 error when data are bad/unexpected, but it’s important to find ways to validate your data to keep it clean and update any original assumptions that the data may violate.

Now that we’ve got our corpus in place, stay tuned for the next blog post on preprocessing text data!